4 AI policy and U.S.-China relations

4.1 Americans underestimate the U.S. and China’s AI research and development

In this survey experiment, we asked respondents to consider either the U.S. or China’s status in AI research and development (R&D). (Details of the survey experiment are found in Appendix B.) Respondents were asked the following:

Compared with other industrialized countries, how would you rate [the U.S./China] in AI research and development?

By almost any metric of absolute achievement (not per-capita achievement), the U.S. and China are the world leaders in the research and development of AI. The U.S. and China led participation in the 2017 AAAI Conference, one of the important ones in the field of AI research; 34% of those who presented papers had a U.S. affiliation while 23% had a Chinese affiliation (Goldfarb and Trefler 2018). The U.S. and China also have the highest percentage of the world’s AI companies, 42% and 23%, respectively (IT Juzi and Tencent Institute 2017). Most clearly, the U.S. and China have the largest technology companies focused on developing and using AI (Google, Facebook, and Amazon in the U.S.; Tencent, Alibaba, and Baidu in China).

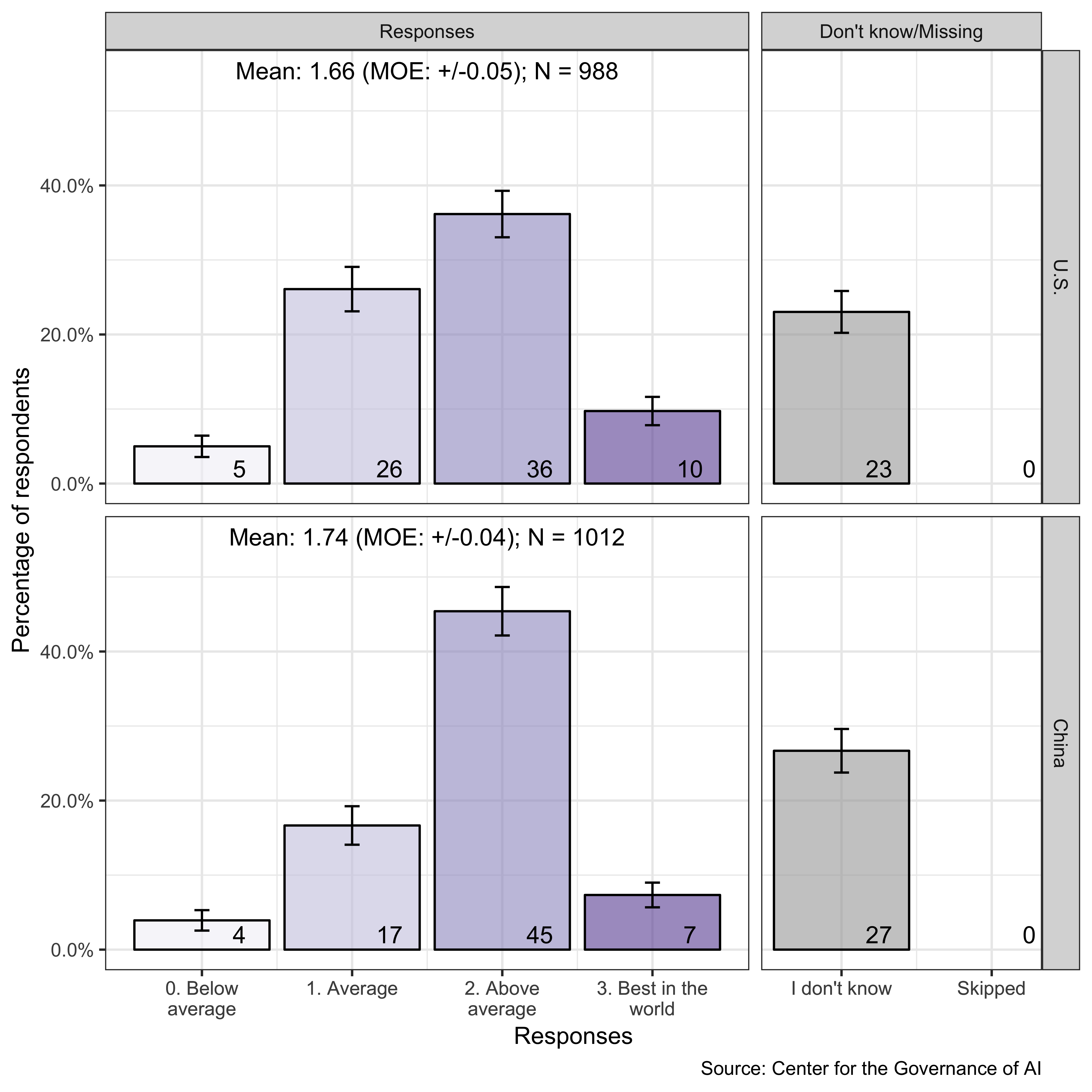

Yet, only a minority of the American public thinks the U.S. or China’s AI R&D is the “best in the world,” as reported in Figure 4.1. Our survey result seems to reflect the gap between experts and the public’s perceptions of U.S.’s scientific achievements in general. While 45% of scientists in the American Association for the Advancement of Science think that scientific achievements in the U.S. are the best in the world, only 15% of the American public express the same opinion (Funk and Rainie 2015).

According to our survey, there is not a clear perception by Americans that the U.S. has the best AI R&D in the world. While 10% of Americans believe that the U.S. has the best AI R&D in the world, 7% think that China does. Still, 36% of Americans believe that the U.S.’s AI R&D is “above average” while 45% think China’s is “above average.” Combining these into a single measure of whether the country has “above average” or “best in the world” AI R&D, Americans do not perceive the U.S. to be superior, and the results lean towards the perception that China is superior. Note that we did not ask for a direct comparison, but instead asked each respondent to evaluate one country independently on an absolute scale Appendix C.

Our results mirror those from a recent survey that finds that Americans think that China’s AI capability will be on par with the U.S.’s in 10 years (West 2018b). The American public’s perceptions could be caused by media narratives that China is catching up to the U.S. in AI capability (Kai-Fu 2018). Nevertheless, another study suggests that although China has greater access to big data than the U.S., China’s AI capability is about half of the U.S.’s (Ding 2018). Exaggerating China’s AI capability could exacerbate growing tensions between the U.S. and China (Zwetsloot, Toner, and Ding 2018). As such, future research should explore how factual – non-exaggerated – information about American and Chinese AI capabilities influences public opinions.

Figure 4.1: Comparing Americans’ perceptions of U.S. and China’s AI research and development quality

4.2 Communicating the dangers of a U.S.-China arms race requires explaining policy trade-offs

In this survey experiment, respondents were randomly assigned to consider different arguments about a U.S.-China arms race. (Details of the survey experiment are found in Appendix B.) All respondents were given the following prompt:

Leading analysts believe that an AI arms race is beginning, in which the U.S. and China are investing billions of dollars to develop powerful AI systems for surveillance, autonomous weapons, cyber operations, propaganda, and command and control systems.

Those in the treatment condition were told they would read a short news article. The three treatments were:

Pro-nationalist treatment: The U.S. should invest heavily in AI to stay ahead of China; quote from a senior National Security Council official

Risks of arms race treatment: The U.S.-China arms race could increase the risk of a catastrophic war; quote from Elon Musk

One common humanity treatment: The U.S.-China arms race could increase the risk of a catastrophic war; quote from Stephen Hawking about using AI for the good of all people rather than destroying civilization

Respondents were asked to consider two statements and indicate whether they agree or disagree with them:

The U.S. should invest more in AI military capabilities to make sure it doesn’t fall behind China’s, even if doing so may exacerbate the AI arms race.

The U.S. should work hard to cooperate with China to avoid the dangers of an AI arms race, even if doing so requires giving up some of the U.S.’s advantages. Cooperation could include collaborations between American and Chinese AI research labs, or the U.S. and China creating and committing to common safety standards for AI.

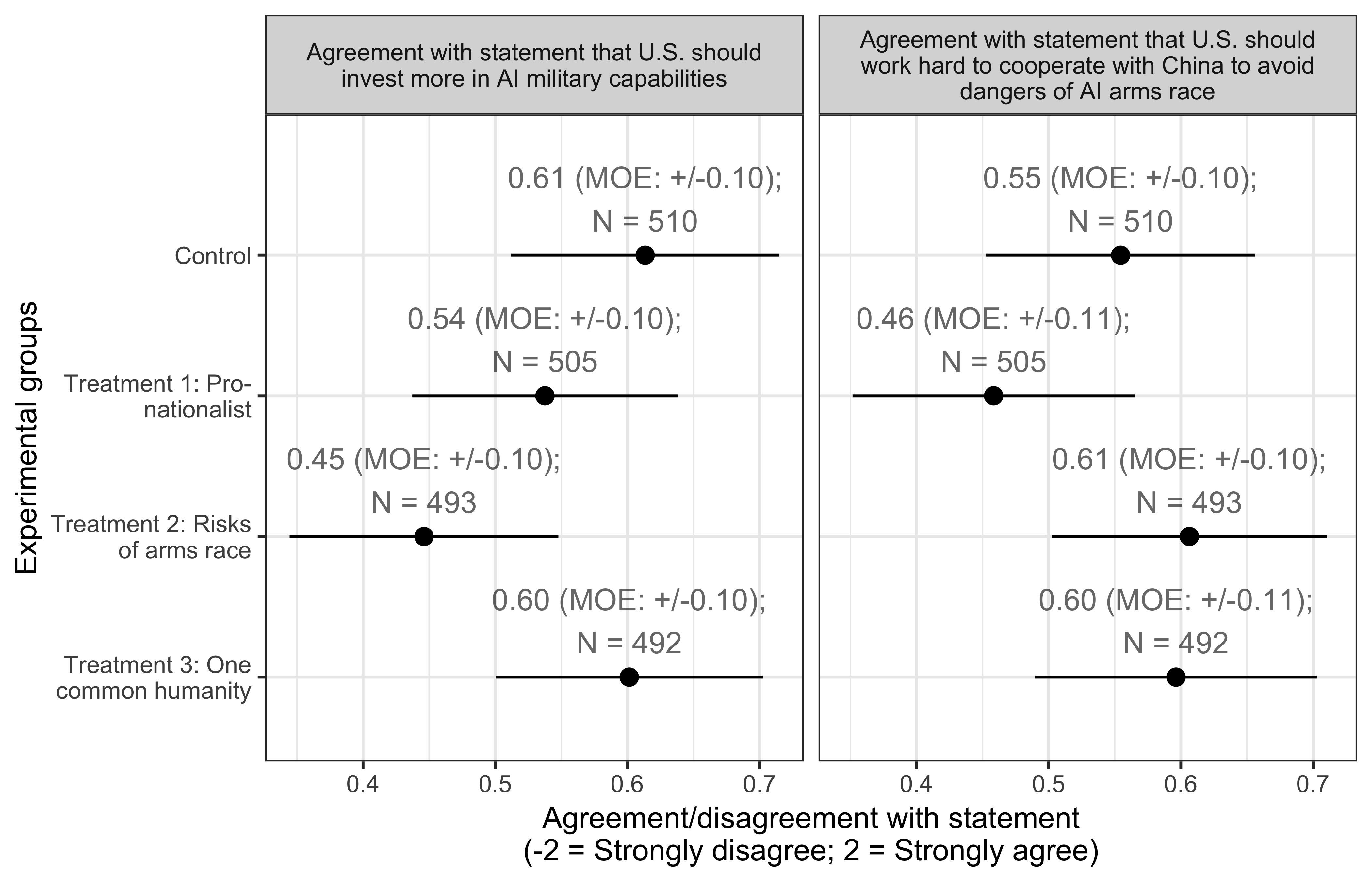

Americans, in general, weakly agree that the U.S. should invest more in AI military capabilities and cooperate with China to avoid the dangers of an AI arms race, as seen in Figure 4.2. Many respondents do not think that the two policies are mutually exclusive. The correlation between responses to the two statements, unconditional on treatment assignment, is only -0.05. In fact, 29% of those who agree that the U.S. and China should cooperate also agree that the U.S. should invest more in AI military capabilities. (See Figure C.2 for the conditional percentages.)

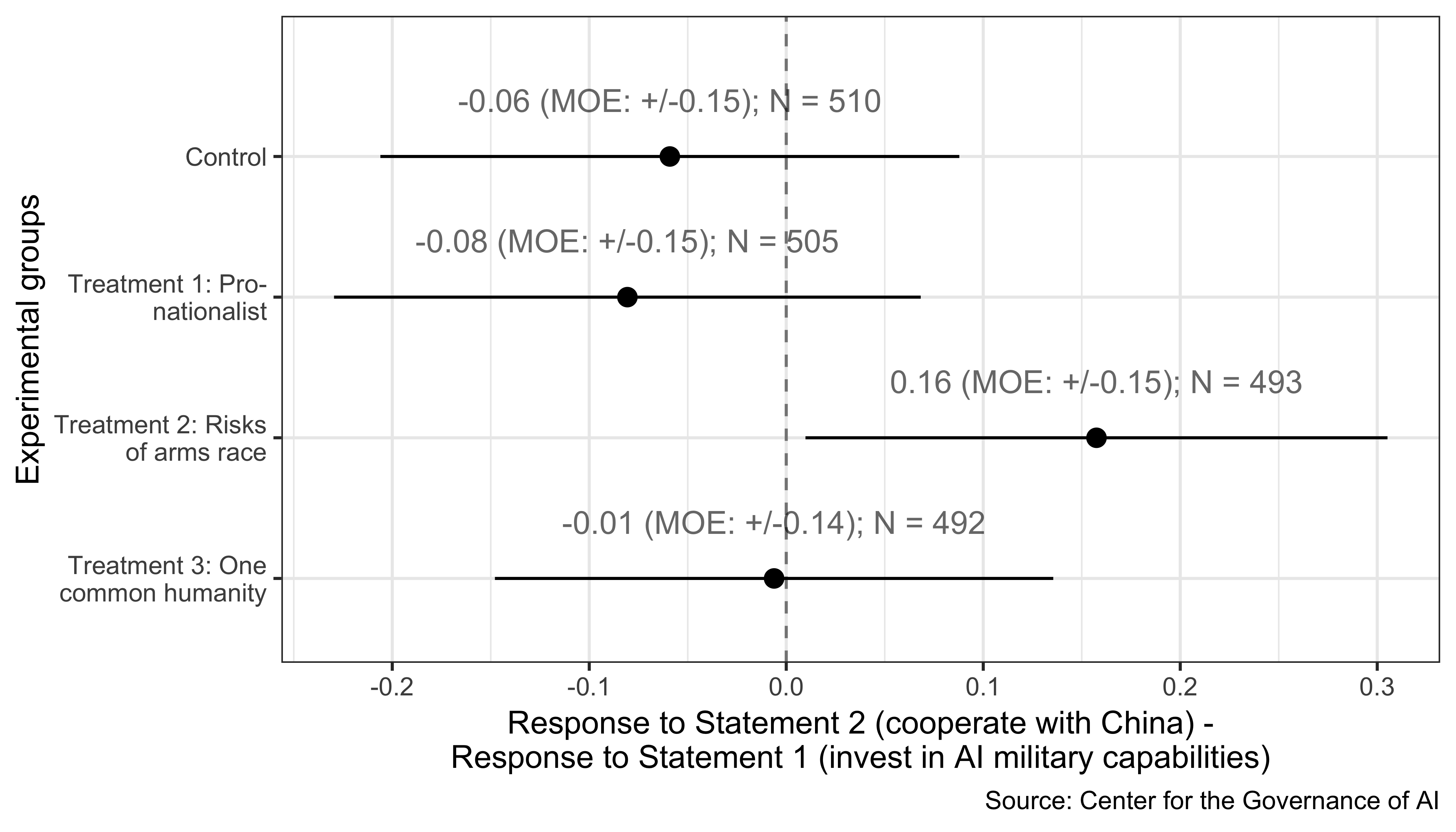

Respondents assigned to read about the risks of an arms race (Treatment 2) indicate significantly higher agreement with the pro-cooperation statement (Statement 2) than the investing in AI military capabilities statement (Statement 1), according to Figure 4.4. Those assigned to Treatment 2 are more likely to view the two statements as mutually exclusive. In contrast, respondents assigned to the other conditions indicate similar levels of agreement with both statements.

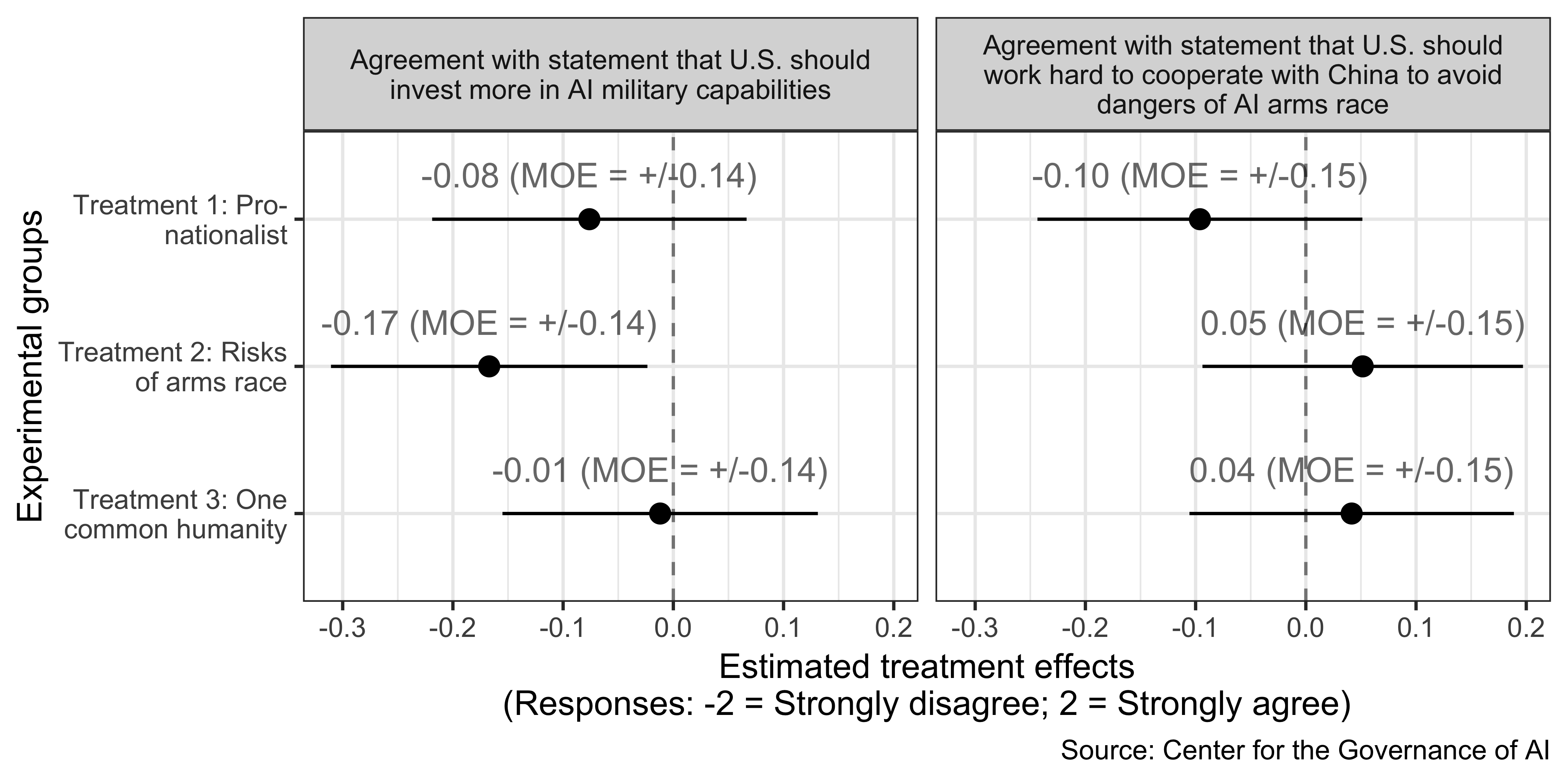

After estimating the treatment effects, we find that the experimental messages do little to change the respondents’ preferences. Treatment 2 is the one exception. Treatment 2 decreases respondents’ agreement with the statement that the U.S. should invest more in AI military capabilities by 27%, as seen in Figure 4.3. Future research could focus on testing more effective messages, such as op-eds (Coppock et al. 2018) or videos (Paluck et al. 2015), which explains that U.S.’s investment in AI for military use will decrease the likelihood of cooperation with China.

Figure 4.2: Responses from U.S.-China arms race survey experiment

Figure 4.3: Effect estimates from U.S.-China arms race survey experiment

Figure 4.4: Difference in response to the two statements by experimental group

4.3 Americans see the potential for U.S.-China cooperation on some AI governance challenges

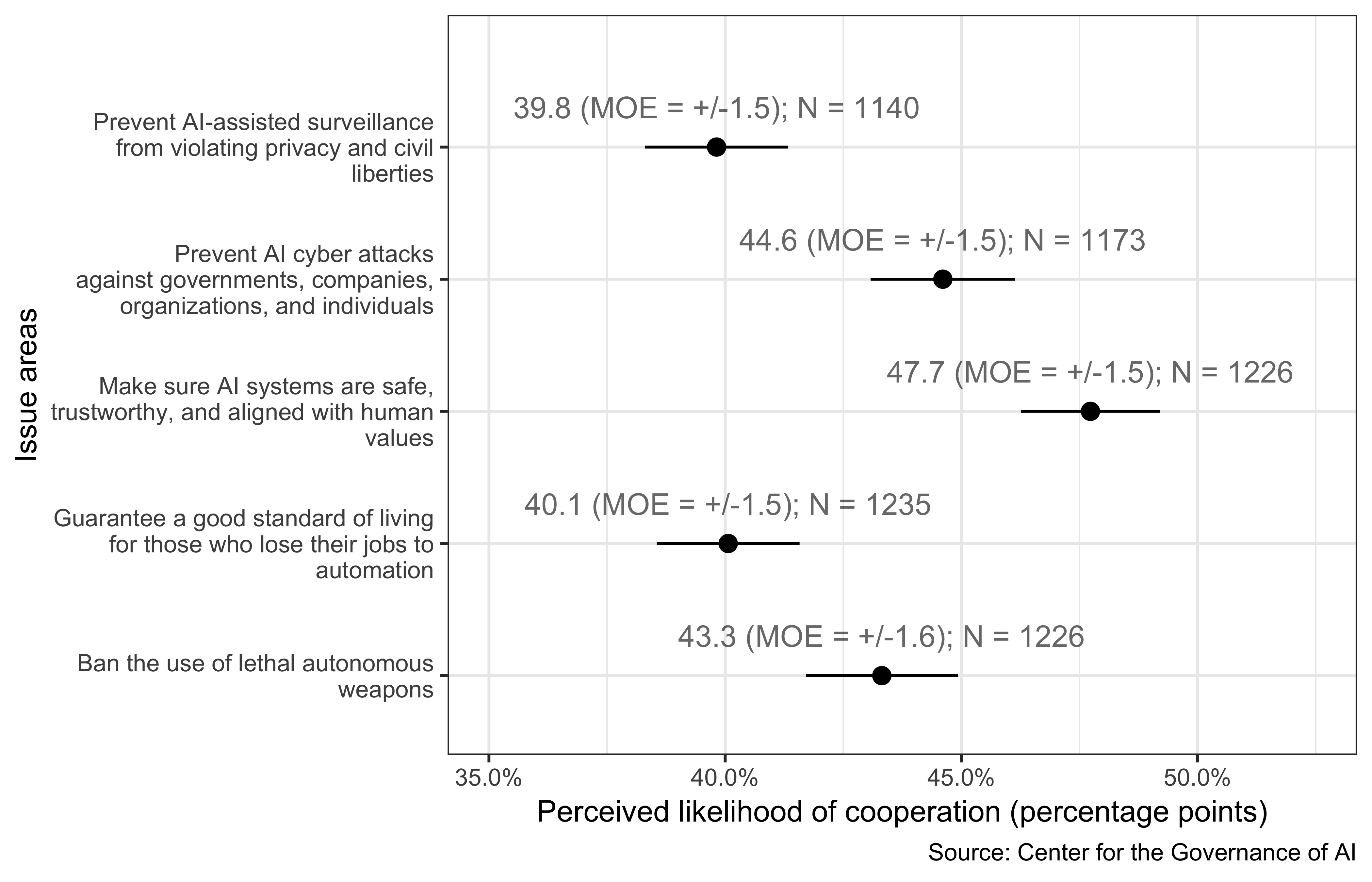

We examined issue areas where Americans perceive likely U.S.-China cooperation. Each respondent was randomly assigned to consider three out of five AI governance challenges. For each challenge, the respondent was asked, “For the following issues, how likely is it that the U.S. and China can cooperate?”. (See Appendix B for the question text.)

On each of these AI governance issues, Americans see some potential for U.S.-China cooperation, according to Figure 4.5. U.S.-China cooperation on value alignment is perceived to be the most likely (48% mean likelihood). Cooperation to prevent AI-assisted surveillance that violates privacy and civil liberties is seen to be the least likely (40% mean likelihood) – an unsurprising result since the U.S. and China take different stances on human rights.

Despite current tensions between Washington and Beijing, the Chinese government, as well as Chinese companies and academics, have signaled their willingness to cooperate on some governance issues. These include banning the use of lethal autonomous weapons (Kania 2018), building safe AI that is aligned with human values (China Institute for Science and Technology Policy at Tsinghua University 2018), and collaborating on research (News 2018). Most recently, the major tech company Baidu became the first Chinese member of the Partnership on AI, a U.S.-based multi-stakeholder organization committed to understanding and discussing AI’s impacts (Cadell 2018).

In the future, we plan to survey Chinese respondents to understand how they view U.S.-China cooperation on AI and what governance issues they think the two countries could collaborate on.

Figure 4.5: Issue areas for possible U.S.-China cooperation

References

Cadell, Cate. 2018. “Search engine Baidu becomes first China firm to join U.S. AI ethics group.” Reuters. https://perma.cc/DC63-9CFT.

China Institute for Science and Technology Policy at Tsinghua University. 2018. “China AI Development Report 2018.” China Institute for Science; Technology Policy at Tsinghua University.

Coppock, Alexander, Emily Ekins, David Kirby, and others. 2018. “The Long-Lasting Effects of Newspaper Op-Eds on Public Opinion.” Quarterly Journal of Political Science 13 (1): 59–87.

Ding, Jeffrey. 2018. “Deciphering China’s AI Dream.” Technical report. Governance of AI Program, Future of Humanity Institute, University of Oxford. https://perma.cc/9BED-QGTU.

Funk, Cary, and Lee Rainie. 2015. “Public and Scientists’ Views on Science and Society.” Survey report. Pew Research Center. https://perma.cc/9XSJ-8AJA.

Goldfarb, Avi, and Daniel Trefler. 2018. “AI and International Trade.” In The Economics of Artificial Intelligence: An Agenda. University of Chicago Press. https://www.nber.org/chapters/c14012.pdf.

IT Juzi and Tencent Institute. 2017. “2017 China-U.s. AI Venture Capital State and Trends Research Report.” Technical report. IT Juzi; Tencent Institute. https://perma.cc/AMN6-DZUV.

Kai-Fu, Lee. 2018. AI Superpowers: China, Silicon Valley and the New World Order. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Kania, Elsa. 2018. “China’s Strategic Ambiguity and Shifting Approach to Lethal Autonomous Weapons Systems.” Lawfare. https://perma.cc/K68L-YF7Q.

News, Bloomberg. 2018. “China Calls for Borderless Research to Promote AI Development.” Bloomberg News. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-09-17/china-calls-for-borderless-research-to-promote-ai-development.

Paluck, Elizabeth Levy, Paul Lagunes, Donald P Green, Lynn Vavreck, Limor Peer, and Robin Gomila. 2015. “Does Product Placement Change Television Viewers’ Social Behavior?” PloS One 10 (9): e0138610.

West, Darrell M. 2018b. “Brookings survey finds worries over AI impact on jobs and personal privacy, concern U.S. will fall behind China.” Survey report. Brookings Institution. https://perma.cc/HY38-3GCC.

Zwetsloot, Remco, Helen Toner, and Jeffrey Ding. 2018. “Beyond the Ai Arms Race.” Foreign Affairs November. https://perma.cc/CN76-6LG8.