5 Trend across time: attitudes toward workplace automation

Survey questions measuring Americans’ perceptions of workplace automation have existed since the 1950s. Our research seeks to track changes in these attitudes across time by connecting past survey data with original, contemporary survey data.

5.1 Americans do not think that labor market disruptions will increase with time

American government agencies, think tanks, and media organizations began conducting surveys to study public opinion about technological unemployment during the 1980s when unemployment was relatively high. Between 1983 and 2003, the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) conducted eight surveys that asked respondents the following:

In general, computers and factory automation will create more jobs than they will eliminate. Do you strongly agree, agree, disagree, or strongly disagree?

Our survey continued this time trend study by posing a similar – but updated – question (see Appendix B):

Do you strongly agree, agree, disagree, or strongly disagree with the statement below?

In general, automation and AI will create more jobs than they will eliminate.

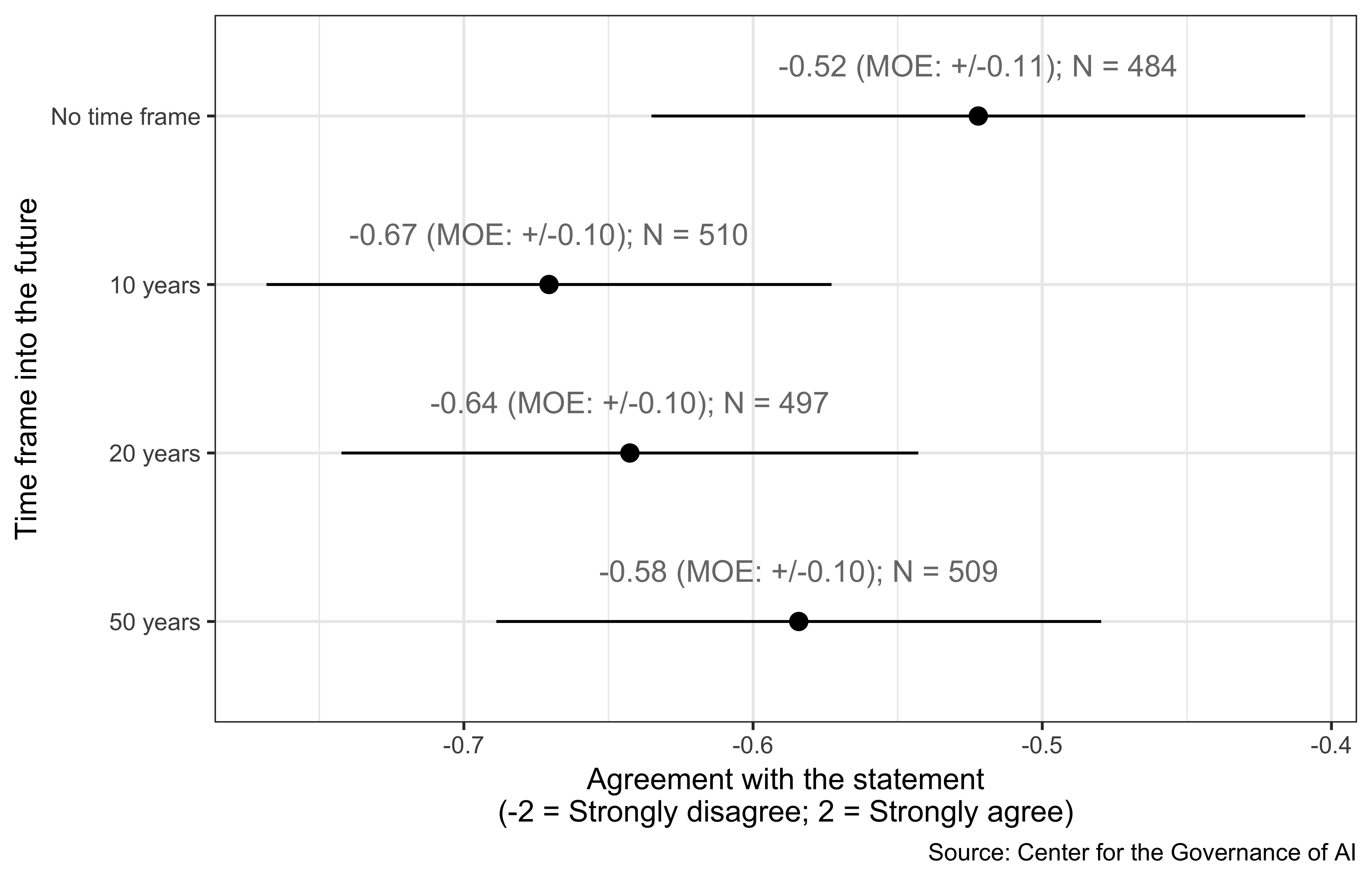

Our survey question also addressed the chief ambiguity of the original question: lack of a future time frame. We used a survey experiment to help resolve this ambiguity by randomly assigning respondents to one of four conditions. We created three treatment conditions with the future time frames of 10 years, 20 years, and 50 years, as well as a control condition that did not specify a future time frame.

On average, Americans disagree with the statement more than they agree with it, although about a quarter of respondents in each experimental group give “don’t know” responses. Respondents’ agreement with the statement seems to increase slightly with the future time frame, but formal tests in Apppendix C reveal that there exist no significant differences between the responses to the differing future time frames. This result is puzzling from the perspective that AI and robotics will increasingly automate tasks currently done by humans. Such a view would expect more disagreement with the statement as one looks further into the future. One hypothesis to explain our results is that respondents believe the disruption from automation is destabilizing in the upcoming 10 years but eventually institutions will adapt and the labor market will stabilize. This hypothesis is consistent with our other finding that the median American predicts a 54% chance of high-level machine intelligence being developed within the next 10 years.

Figure 5.1: Agreement with the statement that automation and AI will create more jobs than it will eliminate

5.2 Extending the historical time trend

The percentage of Americans that disagrees with the statement that automation and AI will create more jobs than they destroy is similar to the historical rate of disagreement with the same statement about computers and factory automation. Nevertheless, the percentage who agree with the statement has decreased by 12 percentage points since 2003 while the percentage who responded “don’t know” has increased by 18 percentage points since 2003, according to Figure 5.2.

There are three possible reasons for these observed changes. First, we have updated the question to ask about “automation and AI” instead of “computers and factory automation.” The technologies we asked about could impact a wider swath of the economy; therefore, respondents may be more uncertain about AI’s impact on the labor market. Second, there is a difference in survey mode between the historical data and our data. The NSF surveys were conducted via telephone while our survey is conducted online. Some previous research has shown that online surveys, compared with telephone surveys, produce a greater percentage of “don’t know” responses (Nagelhout et al. 2010; Bronner and Kuijlen 2007). But, other studies have shown that online surveys cause no such effect (Shin, Johnson, and Rao 2012; Bech and Kristensen 2009). Third, the changes in the responses could be due to the actual changes in respondents’ perceptions of workplace automation over time.

![Response to statement that automation will create more jobs than it will eliminate[^jobsqfn] (data from before 2018 from National Science Foundation surveys)](ai_public_opinion_us_2018_report-190107_web_files/figure-html/jobscompare-1.png)

Figure 5.2: Response to statement that automation will create more jobs than it will eliminate11 (data from before 2018 from National Science Foundation surveys)

References

Bech, Mickael, and Morten Bo Kristensen. 2009. “Differential Response Rates in Postal and Web-Based Surveys in Older Respondents.” Survey Research Methods 3 (1): 1–6.

Bronner, Fred, and Ton Kuijlen. 2007. “The Live or Digital Interviewer - a Comparison Between CASI, CAPI and CATI with Respect to Differences in Response Behaviour.” International Journal of Market Research 49 (2): 167–90.

Nagelhout, Gera E, Marc C Willemsen, Mary E Thompson, Geoffrey T Fong, Bas Van den Putte, and Hein de Vries. 2010. “Is Web Interviewing a Good Alternative to Telephone Interviewing? Findings from the International Tobacco Control (Itc) Netherlands Survey.” BMC Public Health 10 (1): 351.

Shin, Eunjung, Timothy P Johnson, and Kumar Rao. 2012. “Survey Mode Effects on Data Quality: Comparison of Web and Mail Modes in a Us National Panel Survey.” Social Science Computer Review 30 (2): 212–28.

Note that our survey asked respondents this question with the time frames 10, 20 and 50 years, whereas the NSF surveys provided no time frame.↩